Are

Vaccines Effective?

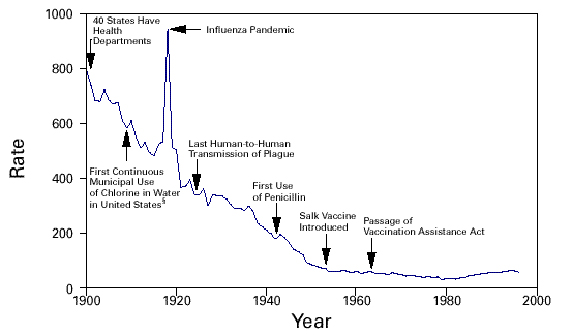

DYI: Right from CDC’s web site and

chart in 1996 before they

got into bed with big pharma admitting the huge fall off of infectious diseases

was the result primarily from clean drinking water. Wide spread use of vaccines didn’t begin until the early 1950’s with the

introduction of the polio vaccine. Not

until the 1960’s vaccines were used by the public on a widespread basis; by that time infectious diseases had already been reduced years earlier by a significant degree 90% plus through public health infrastructure.

Any health

professional who states that taming of those diseases was/is from vaccines is

either grossly misinformed of the U.S. experience [thus not professional] or

simply fabricating the effectiveness of vaccines upon the American example.

History of Drinking Water Treatment

Center for Disease

Control – CDC – Web Site

A Century of U.S. Water Chlorination and Treatment: One of the Ten Greatest Public Health Achievements of the 20th Century

American drinking water supplies are among the safest in the world. The disinfection of water has played a critical role in improving drinking water quality in the United States. In 1908, Jersey City, New Jersey was the first city in the United States to begin routine disinfection of community drinking water. Over the next decade, thousands of cities and towns across the United States followed suit in routinely disinfecting their drinking water, contributing to a dramatic decrease in disease across the country (Fig 1).

Center for Disease

Control – CDC – Web Site

The occurrence of diseases such as cholera and typhoid dropped dramatically. In 1900, the occurrence of typhoid fever in the United States was approximately 100 cases per 100,000 people. By 1920, it had decreased to 33.8 cases per 100,000 people. In 2006, it had decreased to 0.1 cases per 100,000 people (only 353 cases) with approximately 75% occurring among international travelers. Typhoid fever decreased rapidly in cities from Baltimore to Chicago as water disinfection and treatment was instituted. This decrease in illness is credited to the implementation of drinking water disinfection and treatment, improving the quality of source water, and improvements in sanitation and hygiene.

It is because of these successes that we can celebrate over a century of public drinking water disinfection and treatment – one of the greatest public health achievements of the 20th century.

The facts are clear: infectious disease deaths declined nearly 90% BEFORE vaccines were introduced…

How is this possible? The pharmaceutical/medical industry has spent MILLIONS convincing us that vaccines saved us all from imminent disease death, but history proves this is more of a marketing tactic than a fact. A marketing tactic that helps ensure the nearly $60 BILLION vaccine market keeps growing.

Why Did Diseases Decline?

The 19th-century population shift from country to city that accompanied industrialization and immigration led to overcrowding in newly populated cities that lacked proper sanitation or clean water systems. These conditions resulted in repeated outbreaks of cholera, dysentery, TB, typhoid fever, influenza, yellow fever, and malaria.

By 1900, however, the incidence of many of these diseases had begun to decline because of public health improvements, implementation of which continued into the 20th century.

Sanitation & Hygiene

Local, state, and federal efforts to improve sanitation and hygiene reinforced the concept of collective “public health” action (e.g. to prevent infection by providing clean drinking water). By 1900, 40 of the 45 states had established health departments. The first county health departments were established in 1908 (6).

From the 1930s through the 1950s, state and local health departments made substantial progress in disease prevention activities, including sewage disposal, water treatment, food safety, organized solid waste disposal, and public education about hygienic practices (e.g. food handling and handwashing).

Chlorination and other treatments of drinking water began in the early 1900s and became widespread public health practices, further decreasing the incidence of waterborne diseases.

Tuberculosis declines WITHOUT a vaccine

The incidence of Tuberculosis (TB) also declined as improvements in housing reduced crowding and TB-control programs were initiated. In 1900, 194 of every 100,000 U.S. residents died from TB — the second leading cause of death — and most were residents of urban areas.

In 1940 (before the introduction of antibiotic therapy), TB remained a leading cause of death, but the crude death rate had decreased to 46 per 100,000 persons. There was never a vaccine for Tuberculosis in the United States. Yet other countries TB rates also decreased before the TB vaccine was introduced.

What does the CDC say? It credits clean water, NOT vaccines…

This report from the Center for Disease Control in the US clearly shows that the decline in disease was due to clean water systems and sanitation — NOT vaccines. This report was written before the CDC became grossly intertwined with the pharmaceutical industry.

CELEBRATING DR. JOHN L. LEAL AND 110 YEARS OF U.S. DRINKING WATER CHLORINATION

High rates of waterborne disease and death—especially among infants and small children—were a tragic fact of life in the rapidly urbanizing landscape of Jersey City and elsewhere in the United States of the early twentieth century. We now know that a cycle of waterborne illness is virtually inevitable when upstream communities discharge untreated sewage to rivers and streams that are then used as untreated drinking water sources by downstream communities. In 1904, a new, untreated water supply for the over 200,000 residents of Jersey City was secured from the nearby Boonton Reservoir, and not surprisingly, the high waterborne disease death rates persisted. But that was all about to change.

John Laing Leal was a New Jersey physician, a health officer for the nearby City of Patterson, and sanitary advisor to the Jersey City Water Supply Company. He had witnessed and experienced personal loss from waterborne disease. Dr. Leal was also a student of microbiology, which was still in its infancy. His laboratory studies convinced him that the addition of a very small amount of “chloride of lime” (calcium hypochlorite) at less than one part per million to drinking water would eliminate the pathogens that were sickening residents in Jersey City.

Brandy Vaughan Ex-Pharma Insider – Vaccine Sales Down Legislate Mandates video 153 News!

DYI

No comments:

Post a Comment